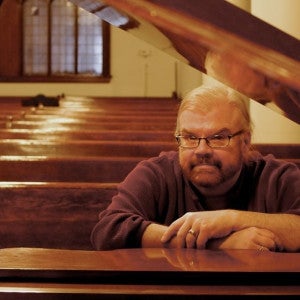

Hearing music on its own terms: Boston Baroque founder Martin Pearlman reflects on his multifaceted musical career

The conductor, harpsichordist, and composer discusses his Interlochen roots, building the Western Hemisphere’s first period instrument ensemble, and his plans for his next chapter.

As Boston Baroque Founder and Music Director Martin Pearlman (IAC/NMC 55, 57) stepped onto the podium for his penultimate performance with the ensemble, he couldn’t help but reflect on the full-circle moment represented by one of the works on the program.

“For the second-to-last concert, we did, among other pieces, Beethoven’s Second Symphony—which I first played when I was at Interlochen,” Pearlman says. “It was the first symphony I’d ever played, and in my last season with Boston Baroque, I programmed it.”

Pearlman’s musical journey has seen its share of unexpected twists between his first and most recent performance of Symphony No. 2. After switching from violin to harpsichord during his undergraduate studies, Pearlman discovered a passion for Baroque music—inspiring him to establish the first period instrument ensemble in the Western Hemisphere.

In May, after 52 years at the helm of Boston Baroque, Pearlman stepped back from his full-time role with the ensemble. We caught up with Pearlman to learn more about his musical roots, career with Boston Baroque, and plans for the future.

Discovering a passion

Pearlman enjoyed a richly musical childhood: He studied violin and piano, and by the time he arrived at Interlochen Arts Camp at age 10, he had already been composing for four years.

“I remember writing a piece for some play that somebody was putting on,” Pearlman recalls. “Don Gillis, who was the composition instructor there, was very good to me. I played violin in the orchestras, and even took my first conducting class there. I learned a lot very quickly, and that’s something I haven’t forgotten.”

During his high school years, Pearlman was invited back to Michigan to join the inaugural Interlochen Arts Academy class, but declined the offer. “At the time, private schools weren’t a thing that most students were doing,” he explains. “But I’ve always wondered what that would have been like.”

After high school, Pearlman enrolled at Cornell University, where he studied composition with Karel Husa and Robert Palmer. In the midst of his sophomore year, Pearlman decided to change his primary instrument.

“I wanted to stop playing the violin, because I just wasn’t happy with my sound,” Pearlman says. “I had a really terrific piano teacher who was off-campus, but as a music major, I was required to take lessons in the department. They wanted me to switch to taking lessons from the pianist in the department, and I didn’t want to do that.”

At a musical crossroads, Pearlman stumbled across a harpsichord.

“It wasn’t a great one, but it was a harpsichord, and I convinced the university organist to teach me lessons on it,” Pearlman says. “I went through The Well-Tempered Clavier and Frescobaldi, all kinds of things.”

Pearlman quickly displayed an aptitude for his new instrument: Just two years later, he was accepted into master’s degree programs at both The Juilliard School and the New England Conservatory as a harpsichordist. He ultimately declined both offers in favor of studying with Dutch keyboardist and early music pioneer Gustav Leonhardt on a Fulbright Grant.

“That was a big turning point for me,” Pearlman says. “[Leonhardt] was just an incredible musician. That’s what got me into harpsichord, and that’s where I first learned about Baroque instruments, too: [Leonhardt] asked me to turn pages for him as he was recording all of the Bach harpsichord concertos. He had a small group accompanying him—just five string players—but they were all playing Baroque instruments, and I was fascinated with that.”

Building America’s first Baroque ensemble

Upon his return to the United States, Pearlman enrolled at Yale University. The school’s robust collection of historic instruments—including harpsichords—further kindled his fascination with Baroque instruments.

After graduating, Pearlman moved to Boston and began playing solo harpsichord recitals. But his interest in playing with a period instrument ensemble lingered.

“I decided to get together all the people I knew who could play decently on Baroque instruments,” Pearlman said. “It was just eight people.”

Audiences warmly embraced the group’s first performances.

“Boston was very receptive to it,” Pearlman says. “We sold out our first series of four concerts right away. The audiences were very curious, very interested. As we started doing bigger, more famous pieces—such as The Messiah or Mass in B Minor—there was tremendous curiosity about what these pieces sounded like on period instruments. People’s interest in this wasn’t an antiquarian interest: It was a modern idea of trying to hear this music in its own terms.”

In the early days of the ensemble, Pearlman and his colleagues faced the challenge of recreating a sound that few modern audiences—or musicians—had ever heard.

“When I first started working on this, there was very little to go by as far as recordings or other groups,” Pearlman says. “A lot of what we learned was from books, from teachers, and by studying and playing the instruments. We had to kind of resurrect this style of playing.”

Over the years, the ensemble continued to evolve in size and scope.

“We gradually added more instruments as they became available—as players came back from Europe or wherever they had studied them,” Pearlman says. “I also convinced a number of players to take up these instruments, and eventually added a chorus so we could do more repertoire. Around the seventh or eighth year, I decided to start doing some opera so that we could do the entire Baroque repertoire. Eventually, we extended into classical works, such as Mozart and Beethoven.”

As Pearlman looks back on his five decades with Boston Baroque, he’s most proud of the ensemble’s many ‘firsts.’

“We did a lot of pieces that had not been played on period instruments since they were written a few hundred years ago,” Pearlman says. “We did the first Don Giovanni in America and the first Mass in B Minor on period instruments. We were the first period ensemble to play in Carnegie Hall. We also played various festivals, including Tanglewood, and we played in the opening season of Disney Hall in Los Angeles.”

The ensemble was also the first period-instrument orchestra signed by Telarc Records, and was the first American orchestra to record with the UK-based Linn Records. Pearlman considers the ensemble’s 25 albums to be particularly special milestones: The records have been commercial and critical successes, garnering six GRAMMY Award nominations.

Embracing a new chapter

As Pearlman transitions out of his full-time role with Boston Baroque, he looks forward to focusing on another aspect of his musicianship: composition.

“Composition has been sort of in the background; it hasn’t been my main public pursuit,” Pearlman says. “There are many people who don’t know that I’m a composer. Now that I’m stepping back from conducting, I’m doing more composing.”

Despite his extensive work with Baroque repertoire, Pearlman’s own compositions are distinctly modern.

“Most of my music is atonal,” he says. “It tends to be narrative in a way—it’s not a minimalist type of thing where you have one note that grows into something else. I just finished a piece for two pianos. I just had a string quartet played, and I recently wrote a three-act work based on James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake.”

Pearlman isn’t closing the book on Baroque music entirely, however: He’s also sharing his expertise as a board member and advisor for North Star Baroque in Portland, Maine—an ensemble recently founded by his daughter, Anna Pearlman.

And although Pearlman is passing the baton to a new conductor, he plans to remain involved with the ensemble he founded 52 years ago.

“I’m still connected to Boston Baroque,” he says. “I’m music director emeritus, but I’ll still provide certain things like program notes or advice as we go into this next chapter.”

“It’s been a long journey, and it’s been great. It’s been terrific to see how this thing has grown.”