Farming from the heart: An Anishinaabe farmer and her Arts Academy student share traditional agricultural practices in Greenacres documentary

A chance encounter between a film crew and a Michigan farm family led one student from regenerative agriculture to animation—and back again.

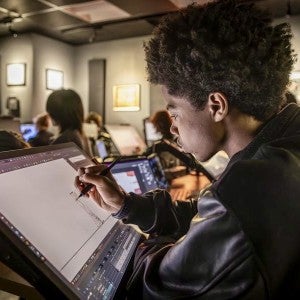

Left: Max Baker, a senior animation student at Interlochen Arts Academy. Right: Mary Donner, Baker's mother and farmer at Mshko’Ode.

When Max Baker watched a film crew pull up to their family’s farm in spring of 2023, they didn’t know it would change the course of their future.

The film crew was from Interlochen Arts Academy, and they were there to work on the Greenacres documentary, which explores the impact of regenerative agriculture on land and people. Max’s mother, Mary Donner, had invited them to the farm to get a closer look at the planting process.

Baker was only there to babysit their younger brother, but when the students took a break from filming, they struck up a conversation.

“ I ended up connecting with some of the students and they told me ‘Come to Interlochen! It's fun here!’ So I said I would look into it,” Baker remembers.

Fast forward to today: Baker is a senior animation student at Interlochen Arts Academy. They’re deeply involved in the Greenacres project, and currently directing animation for a sequence written and voiced by their mother about companion planting. It’s a full circle moment that wouldn’t be possible without a few coincidences and a lot of love for land, community, and culture.

Farming from the heart

Baker's journey to Interlochen has roots just north of Petoskey, Michigan, on a farm called Mshko’Ode (“Strong Heart”). Donner and Baker are both Anishinaabe. For them, the practice of regenerative farming is more than a responsible way to steward the environment. It’s an expression of their family’s Indigenous heritage.

“It's a way of communicating with the earth and connecting to those around us in a way that doesn't harm anybody. It's a way of healing,” says Baker.

Baker’s mother would agree. She initially became curious about organic foods while working at a health food store many years ago. What started with Google searches about food insecurity and growing practices led to further research, farming conferences, and a passion for cultivating healthy soil.

“The rationale behind Mshko’Ode is mostly based on Odawa belief sets. Kevin [Donner’s husband] and I care deeply about all of our relatives—plants, animals, microbes, everything. We wanted to grow food for our family and then for our community in a way that didn't detract from the earth,” she says.

From praying before chicken processing to giving food away to community members in need, Donner makes every part of farming a spiritual practice. Building Mshko’Ode has provided her with an opportunity for her to reconnect with her own Odawa heritage.

“I didn't grow up with those practices, but now I'm finding them in my adulthood,” she says. “It's really cool to realize that even though I stumbled into it through a different path, it’s very aligned with how my ancestors lived.”

A lucky connection and a new path for high school

From the beginning, Mshko’Ode Farm had a strong local impact—but it was soon time for Donner’s efforts to reach a far wider audience. She remembers the day when Claire Collins, producer and co-director of the Greenacres project, gave her a call to see if her crew could film at the farm.

“ I don't normally answer my phone, but for whatever reason I picked it up,” she says. “We ended up having a two-hour conversation.”

Not long after that, Donner found herself on Interlochen’s campus, sharing her knowledge of regenerative agriculture with a room full of eager students.

“That was the first time I’d visited Interlochen’s campus, and I was blown away by how beautiful it was,” she says. “The students were so engaged in what they were learning. They asked in-depth questions that showed a lot of critical thinking.”

Donner couldn’t help but think of her own student. “It reminded me of Max. I knew they would love it here.”

When it was Baker’s turn to visit, they loved the environment too.

“ With the way the campus is set up, I felt like I would be able to focus on my art and focus on bonding with the people around me,” says Baker.

Since they had a background in visual art and had enjoyed working on short animations in the past, Baker decided to major in animation. From the beginning, it was hard work—but to Baker, it was completely worth it.

“ It was quite a bit of work, but in exactly the way I needed it to be. I felt fulfilled and I felt busy in the best way possible,” says Baker.

Sharing an Indigenous perspective

In their second year at Interlochen, Baker had the chance to be a part of the Greenacres project. It made perfect sense to say yes.

“ One of the biggest inspirations for me to be a part of the Greenacres documentary was trying to offer an Indigenous perspective,” they say. “We want to show people that we've been doing this kind of thing since before ‘regenerative agriculture’ was a term.”

The film crew visited Mshko’Ode Farm to cover harvest and planting ceremonies, the use of fish guts as fertilizer, and the traditional Three Sisters garden (corn, beans, and squash grown as companion plants). Baker is now directing a section of the documentary that explains the importance of the Three Sisters. Through the process, they’ve grown more confident expressing their artistic and cultural identities.

“Learning how to talk to people and direct artistic movement was a fun challenge,” says Baker. “And being able to educate people about my culture has also been super rewarding and fun. It’s a big point of pride for me, because it's part of me that I get to share with others.”

When filming wrapped, it marked the end of an unexpectedly meaningful chapter.

“We really built friendships with the Greenacres staff,” Donner reflects. “We shared meals together and we all cared deeply for each other. It was a much more interpersonal experience than I thought it would be.”

Baker’s involvement in the Greenacres project will end with their senior year, but they’re excited to use what Interlochen has taught them in the future.

“I’d like to pursue more arts education. I'm looking to keep it experimental; I don't want to put myself into a box of just animation or just visual arts,” they say.

Baker still returns home on some weekends and takes part in tribal ceremonies whenever they can. Like their mother, they’re looking boldly towards the future—while staying deeply rooted in traditions that began long before their lifetime.