Interlochen Online's next session begins May 6—enroll in any course or certificate program now.

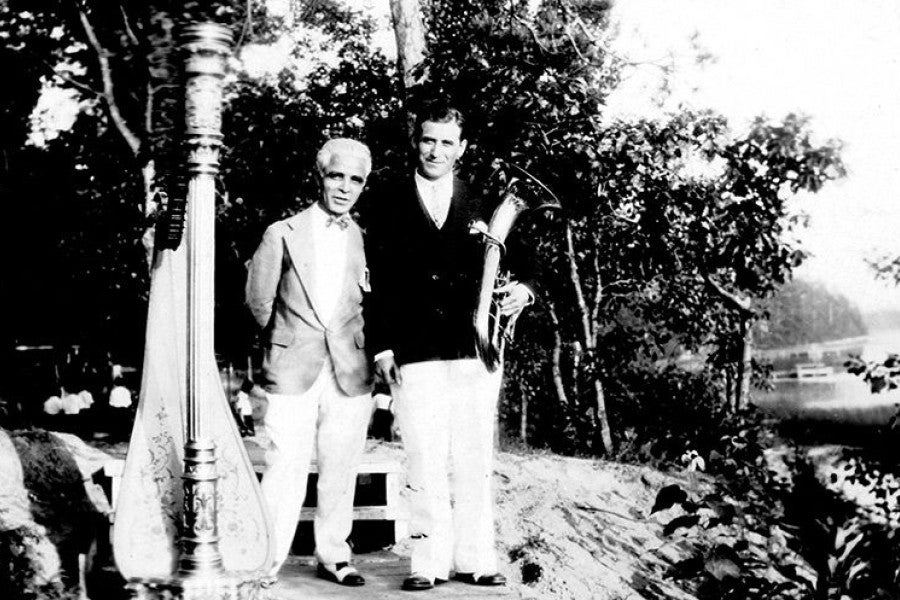

Tradition, fraternity and the Falcone brothers

How Leonard and Nicholas Falcone left their mark on Interlochen in 1928 and on Michigan collegiate athletics for years to come.

The Bears and the Packers. The Lions and the Browns. Notre Dame and USC.

The return of fall weather marks the return of football—and football rivalries. For Michiganders, no rivalry is as important as that between the Michigan Wolverines and the Michigan State Spartans.

What you may not know is that during Interlochen’s inaugural season back in 1928, we played host to two brothers that helped shaped this storied collegiate tradition.

The Falcones’ natural sibling rivalry was intensified by their roles as the band directors at these competing Michigan colleges. Although divided by institutions, the brothers were united by a love of music and a summer as instructors at Interlochen Arts Camp.

Nicholas Falcone was appointed director of the Varsity Band at the University of Michigan in 1927. Several weeks later, Leonard Falcone became the director of the Michigan State College Military Band. For the next seven years, the friendly football rivalry between Michigan and Michigan State would be accompanied by the friendly sibling rivalry of the two band directors.

Joseph Maddy met the Falcones while teaching in the Ann Arbor public schools; Nicholas Falcone actually succeeded Dr. Maddy as director of bands at Ann Arbor High School in 1927. In 1928, Leonard spent the full eight weeks in Interlochen teaching violin sectionals and assuming the conductor’s baton on several occasions. During his time at Interlochen, Leonard Falcone learned to play the baritone. Leonard quickly put his newfound skills to work when on July 8, 1928, he became the first soloist in Interlochen’s history by performing a baritone solo with the National High School Band. Just a few short years later Leonard’s prowess as a baritone soloist was widely known in musical circles. Joseph Maddy himself said, in regard to Leonard, that, “There isn’t a better baritone player in the country.”

Brother Nicholas arrived at Interlochen later that summer, and spent weeks 5-8 with his brother as a founding faculty member.

To sports fans and marching band enthusiasts, Leonard is probably the better-known Falcone, but Nicholas is not without his own achievements. Perhaps the chief of Nicholas’ achievements was launching the career of his younger brother by inspiring his immigration to America and offering him a position in the small pit orchestra he conducted at the time. Nicholas’ lasting legacy, however, was his support of racial and gender integration in the arts. Under Nicholas Falcone’s leadership—and not without a degree of conflict—the University of Michigan concert band allowed women and African Americans to participate for the first time. Nicholas is also known for creating the first script “Ohio” for a halftime show during a game against Ohio State. Falcone’s idea was so good that Ohio State later “stole” the formation for their own pregame show.

The rivalry and collaboration that the brothers shared would not last, however; in the 1930s, Nicholas Falcone began to lose his hearing. By 1934, Nicholas’ hearing loss was so great that Leonard assumed the directorship of both bands, commuting back-and-forth between Ann Arbor and East Lansing multiple times per week. Nicholas officially retired in 1935.

Although Nicholas’ artistic career ended prematurely, Leonard’s continued. At MSU, Leonard followed his brother’s example by integrating the band. During World War II, Leonard filled out his band ranks by inviting women to join the concert band for the first time. They never left even after the war ended. Leonard also contributed to the heritage of the MSU marching band by creating the longer arrangement for Victory for MSU. Known as the “Falcone Fight,” you will still hear it played at MSU athletic events and parades.

Leonard Falcone officially retired in 1967 after 40 years at the helm of MSU’s marching band. He remained, however, an active member of the MSU community, continuing to teach low brass and conducting “MSU Shadows” at home football games.“Leonard Falcone took a military band and transformed it over the years into a trend-setting marching machine and a concert band par excellence, and in so doing, he influenced music around the world,” said Tim Skubick, quoted in Solid Brass: The Leonard Falcone Story by Rita Griffin Comstock. Skubick is a hall of fame broadcaster and a former clarinetist in Leonard Falcone’s band at MSU.

The summer sun would eventually set for the final time over Green Lake that inaugural summer. Even though Nicholas and Leonard Falcone spent only one season on faculty their commitment to collaboration and friendship through music can still be felt through the countless instructors that have succeeded them. Who then could predict that two immigrant brothers turned Michiganders would leave such an important legacy not just on Interlochen but on the artistic world at large?