Expanding the classical canon

The acclaimed conductor and Interlochen alumnus Kazem Abdullah, who will conduct 'X, The Life and Times of Malcolm X' at Michigan Opera Theatre in May, discusses his global career and shares advice for aspiring musicians.

Walking into an auditorium full of people from diverse backgrounds and uniting them in a creative vision is no easy feat, but it’s what drives Kazem Abdullah (IAC 91-93, 95-97, IAA 96-97).

“What is really gratifying is when you’re collaborating with people and you’re learning from them and they’re learning from you, and they’re getting inspiration from you and vice versa,” says Abdullah, a clarinetist and conductor from Dayton, Ohio. “It's a profound and amazing exchange.”

Abdullah has spent nearly two decades bringing musicians together to innovate and grow the classical music canon. A champion of new work, he has infused the field with experimental approaches and global perspectives gleaned from his experience performing and conducting around the world.

“With any art form, I think it’s really important that [classical music] continues to evolve,” Abdullah says. “It has to relate to present-day society.”

After graduating from Interlochen Arts Academy in 1997, Abdullah earned his bachelor’s degree at the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music and continued his studies at the University of Southern California before landing as a clarinet fellow at the New World Symphony in Miami Beach. He went on to perform with orchestras across the country, including those of Oregon, Indianapolis, Detroit, Pittsburgh, and Cincinnati, as well as with prominent international chamber ensembles such as the Paris-based Trio Wanderer. He has conducted in cities ranging from Amsterdam to Cape Town and has performed over 25 operas. From 2012 to 2017, Abdullah served as music and artistic director of the City of Aachen in Germany, where he experimented with new stylistic formats and nontraditional venues and was twice nominated as the best conductor and orchestra in Germany by the newspaper Die Welt.

We spoke with Abdullah about his passion for new and original works, his success around the globe, and how Interlochen opened up a world of possibilities.

You recently conducted the American premiere of Charles Wuorinen’s opera Brokeback Mountain with the New York City Opera, and frequently advocate for new music. What inspires your passion to expand the traditional classical music repertoire?

The present day is always expressed through its art. So the things that are produced by artists of various types today reflect the frame of mind— the worries, the joys —of the people of our time. Art is just such an important document in that sense: It gives a historical context to the era in which it was written. So while I love to do the old standards of Bach and Brahms and Copland and Bernstein, it’s important that we try to find what that next great piece of work will be. And the only way you do that is by championing new composers and new music.

In May you’ll conduct fellow Interlochen alumnus Davóne Tines at Michigan Opera Theatre’s production of X, The Life and Times of Malcolm X. What do you find most exciting about this work?

There are certain operas about historical figures—for instance, Anna Bolena and Maria Stuarda (by Donizetti), or Falstaff (by Giuseppe Verdi)—and they seem so far away that it’s hard to relate.

But most people living today, especially if you’re American, are aware of Malcolm X and what he stood for. This opera is interesting because … it’s probably one of the few works that, in an operatic and mystical setting, tells the story of a Black American in the mid 20th century. It’s a snapshot not only of Malcolm X, but of the mentality of America and the problems of America. And that’s why I think even though the opera is about Malcolm X, it goes beyond that to dramatize the problems that all kinds of human beings experience and how they navigate those problems to try to solve them. Through the telling of the Malcolm X story, the opera really tells a very human story of evolving and of fighting for a better life for oneself and one’s people.

What do you hope audience members will take away from your performances of X, The Life and Times of Malcolm X?

I know for a fact they’ll be moved by the music. It’s an amazing score because it melds American modernist music with American jazz. It’s a uniquely American opera and American work. And I hope that people come away from it having a sense of how American society has evolved in some ways and how, in other ways, American society hasn’t evolved as much as we would like to think.

You’ve established a career performing around the world. How do you navigate cultural differences?

It’s about recognizing that the world is vast and that there are different value systems, but also recognizing how we’re all the same. So whether you live in Asia or Africa or America or Europe or South America, you experience joy and sadness and tragedy and heartache and pain and suffering. And it’s just how various cultures deal with [those emotions].

How did your experiences at Interlochen influence your artistic journey and career?

I learned how to build friendships, how to build relationships, and how to relate to different people. Having Academy students and campers from around the world come together and play music—that’s very much a character-building process.

Do you have a favorite Interlochen memory?

One memory that comes to mind was from my first or second year at Interlochen. It was my first time ever going to a music library; I was 12. I wanted to listen to Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 5. I was like, “I have to learn this first clarinet part so that I can [work] to become the first clarinet.” I went to the librarian—her name was Alice—and the first thing out of her mouth was, “Why don’t you get the score?” And I was like, “Oh, what’s that?” And she said, “It has all of the instruments in it.” So then she gave me this mini score for Tchaikovsky 5. I had to figure out where my part was! But hearing everything and seeing that it’s all there, just opened up a new world.

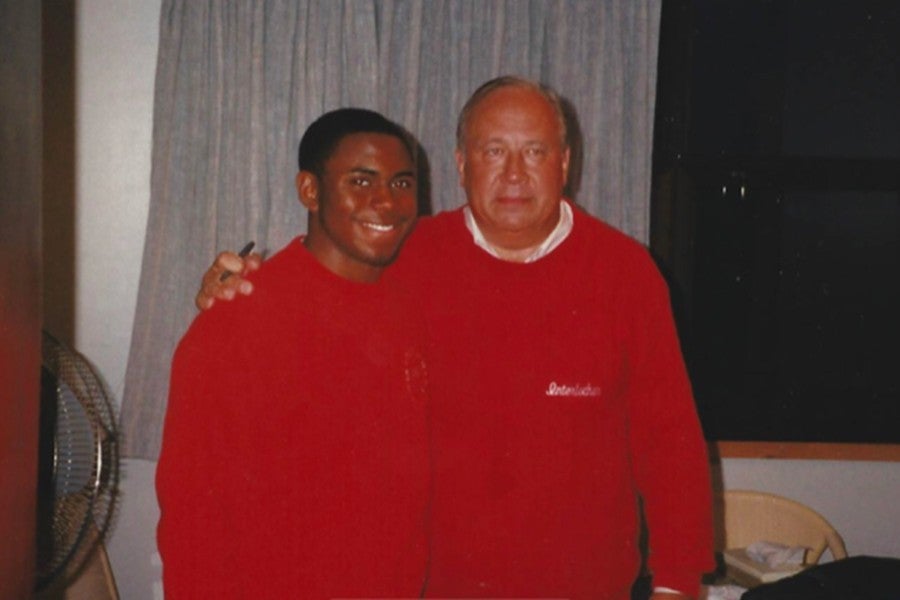

Another great memory I have is from a conducting class I took with the music and artistic director of the World Youth Symphony Orchestra, Henry Charles Smith. He was a former trombonist in the Philadelphia Orchestra. He provided a really good foundation of how to listen to music, how to analyze music, how to play from a score at the piano. To learn these things as a 15- or 16-year-old, these fundamental things, made me the musician I am today.

What would your advice be for young musicians who are looking to expand the classical music repertoire?

Make sure you really understand the building blocks. The ones who have longevity are the ones who have a good foundation, and an understanding of how music works. Just like there are only so many letters in the alphabet, there are only so many notes in music. It’s about how you use those combinations of notes and your command of those notes, and having the technique to know how to use them.